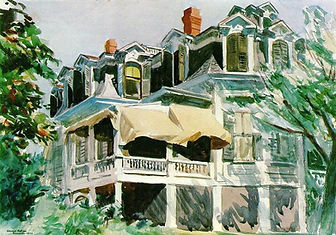

Clarendon Street — Edward Hopper

Bickford's at Smith Cove — Emile A. Gruppé

Georges Bank is a nineteenth-century tale of determination and survival.

A bright but naive Irish immigrant, Maggie O'Grady is impregnated and discarded in a brothel by her first employer in the New World, a rich Boston merchant. With the help of the women around her, Maggie struggles, raises her son, and eventually finds love with a fisherman.

Georges Bank is set in Gloucester, Massachusetts, home to Kipling’s Captains Courageous and Junger’s Perfect Storm, in the days of sail during and after the Civil War. Thousands of Gloucester fishermen died at sea during that time — fighting in the trenches of war was safer than fishing on Georges and the other offshore fishing banks. Life was perilous for those left ashore as well, where the widows and their daughters, left with no legitimate means of support, were sometimes forced into lives of prostitution to survive.

The book climaxes with a wrongful death trial brought by the widows and children of two fishermen killed in a winter storm on a boat insured by the Boston merchant. Maggie’s son, by then a young lawyer, represents the widows. The trial presents a sobering look at the American justice system, its entanglement with the interests of the rich, and the harsh consequences of that inequity for the least powerful among us.

Georges Bank is a rip-roaring good story. The all-too-short lives of the fishermen are realistically portrayed, but so is the romance of a life lived at sea. The plight of the desperate women left behind is realistically shown as well. But there is kindness amidst the violence. By and large, they band together, sometimes in relationships that must be kept secret due to the norms of the time, and they persevere.

Finally, this is the story of a woman who refuses to be a victim, who fights and strives and overcomes.

Available at your favorite

independent bookstore:

And at Amazon:

Inner Harbor — Elizabeth G. Bradley

BRADLEY BAGSHAW

Author

The Physicist

The Physicist is a story of midlife love and regeneration, a romance wrapped in international intrigue and served with a generous helping of government malfeasance.

A University of Washington physics professor is caught up in a clandestine CIA operation that is inspired by a partially declassified government project from the sixties called the “Nth Country Experiment,” in which the U.S. government hired two physicists to determine whether they could design an atomic bomb without the benefit of classified documents.

Jim Whalen was once a budding physics superstar out to claim his place in history by developing string theory, the grand theory-of-everything. Now in midlife, his research has gone nowhere, he's divorced and lonely, and he has lost hope. But Whalen’s first graduate student reenters his life and hires his old professor to see if he has the skills to design a workable bomb without the benefit of classified information. If Whalen succeeds, the CIA will know it must expand the network of physicists it tracks.

In the midst of this, Whalen takes Eliza Block, a successful lawyer he is teaching to fly, on an adventure to the Alaskan wilderness to deliver a single-engine Cessna. On the red-eye flight back to Seattle, they realize they fall in love.

But all is not what it seems.

Don't Look

Don't Look is the story of the Bergmann family, Carrie, her husband, Kristoff, called Bergie by all, their son, Zach, nineteen, and their two school-age daughters, Emmy and April. Pictures of Zach's seventeen-year-old girlfriend are found by the police on Kristoff's computer, and Bergie is charged with a felony. He must decide whether to take the rap or turn in his son, and Carrie must battle a malicious employer and a corrupt prosecutor if she is to save her family.

Hiroshima

Einstein and Oppenheimer

Edmonds Ferry

The Paper Captain's Daughter

Lily Holmes had a hard start to life. At only four years old, she heard her teenage mother scream to her grandmother: “I could have taken care of it. You made me have her. You keep her. I don’t want her.” Then Lily watched her mother drive out of her life in a rage. Many years later, she learned that her father did not even know he’d fathered a child.

Now, at twenty-six, Lily is a cautious environmental journalist living alone in a Sausalito basement apartment. She writes forgettable articles that few read on topics such as the effect of human hormonal discharges on monkfish and gauzy stories about big-eyed seals. From her estranged mother, Lily learns that her father is a factory trawler captain accused of recklessly charging through an Alaskan walrus habitat. Determined to meet him, she travels to Seattle ostensibly to write about corporations endangering protected wildlife. She discovers her father is caught in a web of bribery, political payoff, and environmental desecration. When the fishing company learns Lily is snooping around, its hired thug pursues her and threatens her with ruin and disfigurement.

Lily’s best friend, Cassie, and her family are allies, and she soon meets Joe, a young lawyer suing the same fishing company for abusing its underpaid and overworked employees. Joe’s wit and strong family ties attract Lily, but she fears commitment and broods over Joe’s conservative politics and strong Catholic faith. He would surely be appalled if he learned of her past secrets, and their growing love would be in jeopardy.

Ultimately, Lily must overcome her fear of abandonment to build a relationship with her father and Joe. She must summon the courage to expose the ruthless fishing company and finally earn the journalistic recognition she deserves.

Orcas in the Salish Sea

Factory Trawler

BRADLEY BAGSHAW

I have lived with the sea since exploring Gloucester Harbor at age ten in a beat-up dory that I owned with Tommy Gray. We paid forty-five dollars for that boat — I raised my share from an early morning paper route delivering the Boston Herald Traveler. Back in those days, it got so cold in the winter that the inner harbor skinned over with ice. I still remember putting frozen toes next to the radiator after predawn newspaper deliveries.

My first real job was as an assistant sailing instructor at sixteen. I was assigned the task of teaching fifteen-year-old girls how to race International 110s. I have often said, only partly in jest, that it was the best job I have ever had. Next were four years of summer jobs on the Gloucester docks, first as a stevedore and then as a forklift driver. The latter is one of the few jobs where you alternate between twenty below zero in the warehouse and eighty above on the dock. On humid days it snowed at the freezer door when we opened it to drive a pallet of frozen fish in or out.

After nine years in the Gloucester public schools, my dad decided that boarding school was the place for me, so I went away to the Phillips Exeter Academy at age fifteen. I found out later that mom cried all the way home on the drive back after she and dad had dropped me off.

The first year at Exeter was the hardest of my life. I had always gotten excellent grades in the Gloucester school system. At Exeter, I nearly flunked out of English my first year, and I was required to repeat Latin 1. After getting an A in Gloucester High School, I got a C+ the second time around at Exeter. To say it was demoralizing is to understate the angst of it all. By my third year, I had adjusted, and I will be forever grateful that I learned to write while there. I had been mostly a science geek, still am, I guess, and would never have branched out if I hadn’t been forced to do so. David Weber, barely out of college, was one of my English teachers. Seven years ago, I reconnected with David, now retired from a long and esteemed career teaching at Exeter. He has helped me immensely in my new career as a writer. One of the great joys of my life has been renewing my friendship with him.

After Exeter, I went to Bowdoin College, where I majored in physics and mathematics, and then to MIT, intending to get a graduate degree in physics. But I changed course and got a law degree from Harvard instead. After law school, I moved to Seattle and have had a career as a trial lawyer, often suing fishing companies for mistreating their fishermen. My clients were men and women who endured great hardship under harsh conditions that resembled nineteenth-century Charles Dickens more than twenty-first-century America. They had little economic power, no clout, and too often were badly abused. Many Seattle fishing company executives will disagree, but I always felt good about what I was doing. By and large, it was a great way to make a living.

In 2004, I had the privilege of being the lead trial attorney for eight gay and lesbian couples asserting their claim to marriage rights equal to those granted heterosexual couples. I am proud to say we prevailed at trial, the first time those rights were established in Washington. Sadly, we lost five votes to four in the Washington Supreme Court. My clients had to wait until Washington voters were granted equal rights via the ballot a few years later, and men and women across the country had to wait a few more years until the U.S. Supreme Court made equality the rule nationwide.

Starting in 2007, my wife, Sally, and I took a sabbatical to sail eleven thousand miles from Seattle to Tahiti and back on the thirty-nine-foot cutter Pax Vobiscum, named after a Latin benediction (“peace be with you”) that my brother and I often heard our dad say during moments of agitation. Most of our friends and family members warned Sally and me against confining ourselves in a tiny sailboat on ocean passages of up to twenty-five days out of sight of land. Too much togetherness, everyone told us, too easy to ruin a marriage. Not for us, though; it made our bonds stronger.

Taking a sailboat across an ocean was a lifelong dream for me. My other lifelong dream was to write a novel, and as the sailing trip wound up, I decided to do just that. I started writing Georges Bank, which plays off my knowledge as a sailor and lawyer, on my return to Seattle. After I finished that book, I wrote THE PHYSICIST, which also draws on my experience as a lawyer, as well as my knowledge of flying light aircraft and my physics education, followed by YOUR HUSBAND OR YOUR SON, about a family torn apart by an unfair prosecution and an overreaching law, and then by my latest manuscript, PAPER CAPTAIN'S DAUGHTER, a young woman's quest to find family and expose corruption in the Alaskan fishing industry.

These days I am a full-time writer and retired lawyer.

I also devote time to a not-for-profit that funds research into finding a cure for FSHD, a type of muscular dystrophy. I have the disease. When I was a teenager, it took away my ability to raise my arms over my head, and these days it is slowly depriving me of my ability to walk.

No tears, though. I’ve learned how to use walking sticks, people open doors for me, and I qualify for one of those blue stickers that get you the good parking places.

Life is grand.

Bradley Bagshaw

On the Gloucester Docks — 1958

Exeter

Marriage Equality — 2004

Off Bora Bora — 2008